Anyone interested in modern art, particularly minimalism (i.e., the works of Donald Judd, Ellsworth Kelly, or Richard Serra), is familiar with the question, “This work is pretty, but I don’t get it. What does it mean?” The frustration with minimalism among much of the public1 appears to be universal. For a given work to have meaning (and be meaningful), it must state something clearly to the viewer, allowing them to have some sort of epiphany while viewing the work in their gallery of choice and walk out a more informed individual, with some commentary on a given issue that is certain to be a hit at the next dinner party or social event they attend. “I saw this work at the DeYoung; it was so profound, the way it commented on…” etc.

The need for works to contain meaning—a “message in a bottle” of sorts—often reduces a work to the intent of the artist, removing the viewer. Arguments ensue over whose interpretation of the meaning is right and whose is wrong. “No, I don’t think that’s what he meant here,” or “she obviously meant something different; otherwise, she wouldn’t have put that brushstroke there.” As Susan Sontag argues in her 1964 work Against Interpretation, this theory of “meaning” relies on the idea that a work of art is “composed of items of content” rather than existing as an object itself. To interpret a work of art, Sontag claims, one must sustain the theory that a given work has “content” and that content has some meaning. Sontag says the only way to claim a work has content is to approach it with the intent of interpreting it, thus devaluing the work itself.

But what about works that reject the idea of interpretation from the get-go? Many minimalists, for instance, seek to remove content from a piece by working in simplistic forms. That is, to remove the content, the work is made simpler. Richard Serra, for instance, used massive steel plates to create his minimalist sculptures. Beginning in the 1960s, Serra created hundreds of sculptures, many installed in public places, available to all. Serra’s works interact with their location – they are installed in museums, skyscrapers, fields, beaches, and everywhere in between. They can be massive, breathtaking, and intimidating, or they can be smaller, subdued, and almost hidden.

Serra is also not afraid to be controversial. His 1981 work Tilted Arc, an 120-foot long steel plate crossing the center of Manhattan’s Foley Plaza, stood at 12-feet high, blocked views across the plaza, and undoubtedly transformed the space. After years of public outcry, and a federal lawsuit, the work was removed. Like many other pieces designed by Serra, it was designed for the space, and has not been displayed since. Often, that’s part of the work – his slabs of steel can make you feel angry, uncomfortable, aghast, or calmed, often all in the same piece.

The lesser-known work of relevance for this essay is Sequence (2006), a massive set of two torqued ellipses standing at just over 12 ft high. Sequence features two round end spaces, along with a passage between them. The path makes the shape of a rounded five, twisting back on itself before eventually reaching the other space. The work is built to accommodate people, and viewers are free to walk in and out of the sculpture as they please. First installed at New York’s MOMA in 2007, it was moved to SFMOMA before being loaned to Stanford’s Cantor Arts Center, where it sits today. Sequence lives in the back courtyard of the Cantor, where it is hidden from the road by the Cantor building and various shrubs. Sequence is an example of a work that asks to be experienced rather than interpreted, and thanks to that experience, evokes the unsettling, the disorienting, and the beautifully raw.

As a viewer, Sequence is daunting. The sculpture is tall but also wide, spilling away from the Cantor’s building and cutting into the grass next to it. As one walks around the work, it often towers over them, the slant of the walls bending inwards and outwards. The size of the work means it’s impossible to see all sides at once. Combined with the unusual geometry of the work, the shape is confusing to the viewer. This does not change as the viewer walks inside the work. Thanks to the round, flat surfaces of the work’s centers, any noise made by the viewer is echoed off the walls surrounding them, often amplifying any noise. This, in combination with the fact that the tall walls block most outside noise, makes the usually unnoticeable very noticeable: leaves blowing across the surface of the ground, the shifting of one’s feet on the floor. Functionally, the work reflects the viewer, but uncomfortably so.

The confusion continues as one moves between the two chambers via the five-shaped passageway. In a New York Times article covering his 2007 MOMA show, Serra shows the sculpture to a reporter, who proceeds to get so lost that “[the reporter] had to circumnavigate the exterior to find Serra again.” This experience holds for most viewers as well—Serra’s work is so unintuitive that it’s disorienting. The walls of the passageway tilt inwards and outwards; some sections are wide and open, while others act as a tunnel. Halfway through the passage, it’s almost impossible to orient yourself regarding the sculpture itself. Looking forward, almost all the outside world is blocked by the walls of the work.

At the end of the passageway, the viewer reaches the opposite chamber from the one they started in. This is disorienting. While the southern chamber is slightly larger and wider, the two spaces feel almost identical. The work contains a contradiction: why, if the viewer has moved, does it feel as if they haven’t? The chambers themselves are also unwelcoming, in some way. The bend of the wall means that entering the space is natural and pleasant – the walls seem to flow with the movement of the viewer as they walk into the space. But as the viewer moves to exit the space, this shape reverses. Similar to a fishing trap, the sharp construction of the work ensures a mental effort is required to leave the chamber without bumping into the piece.

Sequence is an exception to a common rule with Serra’s works—they are often built for the space they reside in. These works are meant to be experienced because they augment their space. The installation of Serra’s 1981 work Tilted Arc in Manhattan’s Federal Plaza was famously so controversial that the piece was removed after eight years, primarily due to public hostility. While Sequence was not built for the Cantor, it works within the space it inhabits, augmenting it, and therefore augmenting the viewer’s perception of it.

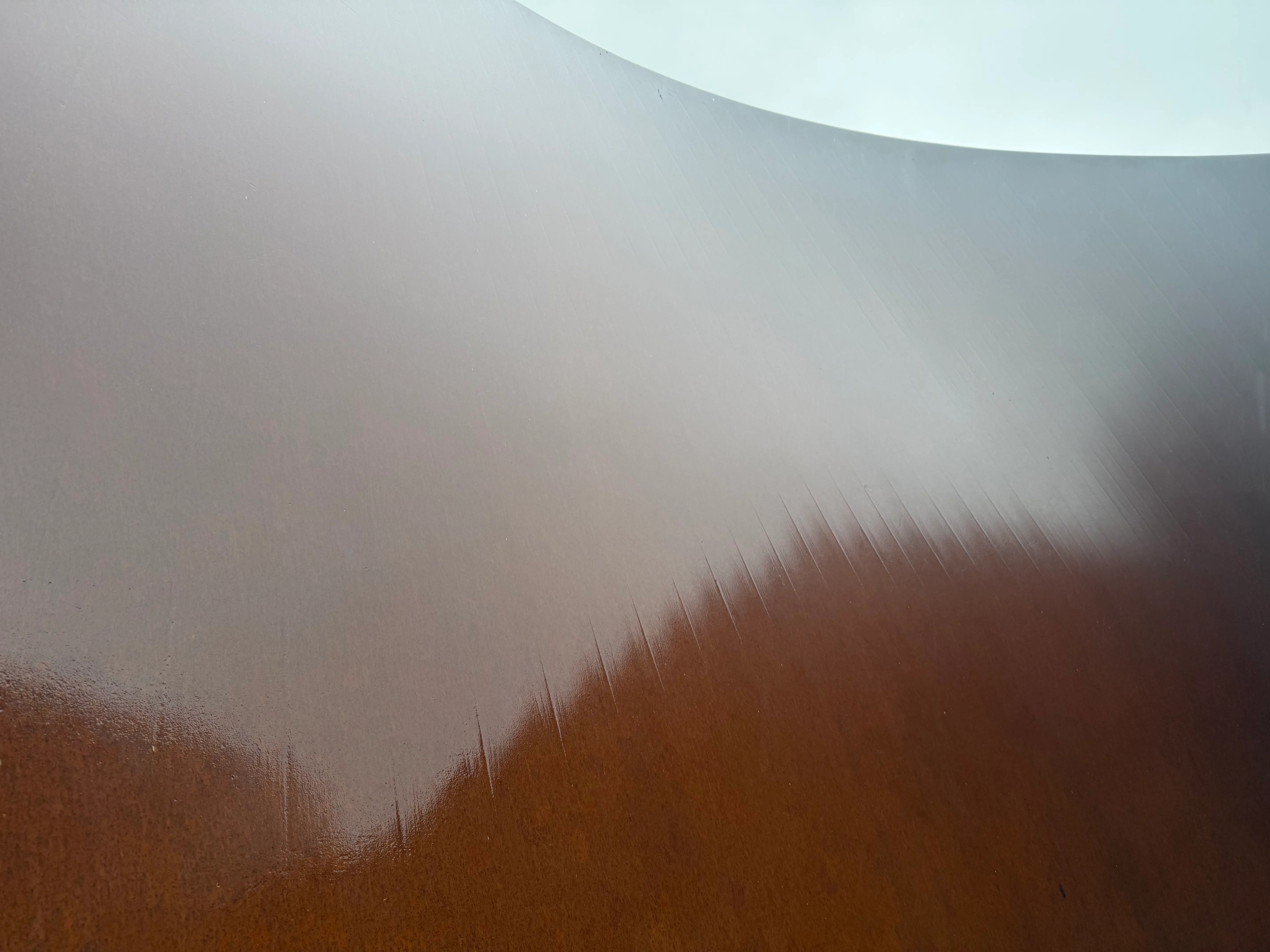

Primarily, Sequence is a large sculpture that works well with its space. The piece is surrounded on one side by the Cantor’s neoclassical building, complementing its Greek aesthetic with a strong minimalist form. The colors are also complementary—the Serra’s deep bronze hue works well with the lighter tan of the Cantor, along with the various trees planted between the work and the building. Sequence also works with light. Because Sequence is located on the west side of the Cantor, the low afternoon sunlight causes the work to cast deep shadows on itself and its environment. While Sequence is mostly smooth, the shadows it casts are not. This makes the work even more intense and contributes to the confusion. Thanks to various gaps in the sculpture, the darkness can often seem overwhelming, especially in the middle passage. When walking between the two chambers, one might round a corner and see a projection of a large spike on the wall.

For the viewer, Sequence can be a truly emotional work; yet the piece contains no content, no greater “message,” no meaning other than raw aesthetic experience. Serra, to this point, agrees with Sontag: he describes Sequence as a work enabled by the viewer. In MOMA’s 2007 exhibition “Richard Serra. Sculpture: Forty Years,” Serra states, “Sequence isn’t here to teach you anything. It’s your experience and what thoughts it engenders; that’s your private participation with this work.” Because one’s experience of Sequence relies on their reflection in it, each individual experiences the work differently. Some may find it daunting, while others may find it comforting. For others, it could be totally irrelevant to how they approach the space. Many works of art require the context of your lived experience, but Serra’s works amplify it.

As part of the documentation of the immediate sensual impact of Sequence, I asked a fellow student to describe their interaction with the work for the first time. The subject, who will remain anonymous, had never seen the work before, and has limited formal training in the arts and art history. Yet, while walking through the work, he described feeling “pulled forward” by a “fascinating double fork”. The passage between the few chambers, distressed him at some points, while at other points he “felt centered.” Some parts of the work made him feel “off-balance,” while at others he felt lost: “I’ve completely disoriented myself as to where we are. And that’s so incredible because now this whole piece feels massive. I feel like we could be anywhere right now.”

In “Against Interpretation,” Sontag discusses the invisible burden of being studied in art: “None of us can ever retrieve that innocence before all theory when art knew no need to justify itself, when one did not ask of a work of art what it said because one knew (or thought one knew) what it did.” Asking what a work “does” is seeking out the naïveté that comes with experiencing art with no preconceptions, allowing yourself to be exposed to the radical reality of the work itself, rather than rationalizing its existence in the context of its creator and a purpose greater than the work. It’s remembering your practice as an art historian can only go so far – in the student interview, the subject had an emotional experience, without knowing anything about the intent of the artist, or ever questioning its meaning.

There is a catch 22: benefitting from this naïveté requires the viewer accept that works can be experiences in themselves, but achieving this principle usually requires some amount of experience with art and art history, as the immediate intuition with a given work is to ask “what does it mean?” So, most art lovers find solace in a proxy. They don’t experience the works themselves, but contemplate what the artist would want the viewer to experience in the work, turning that stone over in their mind for a few moments and then moving onto the next work in the gallery, careful to budget time as MOMA closes soon. Even one who reads Sontag and agrees with her can struggle to put these concepts into practice.

This naturally raises the question: how do we both study art and experience it honestly and fully? I would argue there are two necessities: reaching an internal clearing, where the enjoyment of art is separate from its study and criticism, and rejecting the ego that keeps us there, hidden from the works themselves.

First, we must separate art from its study. Once you approach an aesthetic object as something to be studied, you’ve attached meaning to it: the work is now a means to an end—your studying of art—rather than end in itself. Viewing Sequence through the context of Serra, as an extension of his ethos, prevents the work from actually affecting you. Rather, it forces you into the hypothetical, as you start to use the indefinite pronoun to describe how the work might make one feel. This is no different than assigning meaning to a meaningless work.

To avoid this, we must be entirely present with the work, instead of seeing our meta-interaction from above. We mustn’t leave the gallery to our refuge of art historical knowledge. In Nature, Ralph Waldo Emerson writes of crossing a “bare common,” and enjoying a “perfect exhilaration.” Enjoying a work means being vulnerable, it means opening ourselves up to the possibility of being transfigured, being changed, the work hurting us, damaging us. It forces us to let down our guards, and sit defenseless before the work.

In aphorism 334 of The Gay Science, Nietzsche describes the process of learning to enjoy art (specifically music) as a proxy for learning to love:

“We must first learn in general to hear, to hear fully, and to distinguish a theme or a melody… then we need to exercise effort and good-will in order to endure it in spite of its strangeness… Finally there comes a moment when we are used to it, when we wait for it, when we sense that we should miss it if it were missing; and now it continues to compel and enchant us relentlessly until we have become its humble and enraptured lovers who desire nothing better from the world than it and only it.”

I would argue this is the same for any work of art – we must allow the work to consume us, and allow for the possibility that we become subservient to it. Anything less than this is mere intellectual play.

And so, our largest battle is not with the work, but with ourselves, and our own desires. As Nietzsche writes, this state requires a rejection of the ego as we become the work’s “humble and enraptured lovers.” Truly experiencing a work of art means admitting that the art historian does not control the artwork any more than a mathematician controls the laws of logic, or a physicist controls the functions of our world. Only when we are at the mercy of the universe can it change us for the better.

To conclude: to ask what a work “does” rather than what it means is to ask how the work functions, rather than ask what meaning an individual can derive from it. But understanding what a work does is to ignore the question entirely, and simply be consumed by the piece itself. Of course, the “does” of a work can create meaning—one can find a Serra meaningful despite its lack of “content.” One might find meaning in a personal connection to the work, an emotional reaction it evokes, or a reflective thought that changes their life significantly. Sequence shows that a work can impact the viewer in ways other than containing meaning in itself—to ask what a work “does” is simply a better way of asking its greater purpose, asking what makes the art function as art.

In early 2024, a few days after Serra’s death, I found myself on Manhattan’s West 53rd street for a brief visit to MOMA before meeting a group later in the day. After taking the elevator up to the third floor, I made my way through the Kellys, Newmans, and Rothkos, walked down a flight of stairs, and wandered until I found myself in the center of eight massive metal cubes – Serra’s Equal (2016). Sitting in the center of the empty gallery, unlike every other visit before, I had no intention with the work in front of me. There was no need to analyze the way the cubes are stacked, no need to understand the way the mirrored layout affects the viewer. I didn’t analyze the rust patterns, I didn’t step back and fourth, making small noises with my mouth or commenting on the piece to a friend. For fifteen minutes, I simply stared at the sculpture, it starting back at me. It was deeply personal, deeply emotional, and deeply meaningful – although I had never asked for it to mean anything. Finally, I heard a voice: “Sir, you can’t sit in the gallery.” Reluctantly, grabbing my bag, I stood up, and walked out of the room, a humbled, enraptured, lover of eight metal cubes, caught in the act.

Footnotes

-

This is not to make the case that the public is “stupid” or cannot meaningfully enjoy art without an education. Many people are just approaching the art the wrong way. ↩