“[Greek] art of the late fifth century often seems … devoid of serious content.”

— J. J. Pollitt, Art and Experience in Classical Greece, p. 123

“Ah Dieu ! que la guerre est jolie / Avec ses chants ses longs loisirs.”

(Oh God! How beautiful war is / With his song, his long leisure.)

— Guillaume Apollinaire, “L’Adieu du Cavalier”

She is being taken with grace.

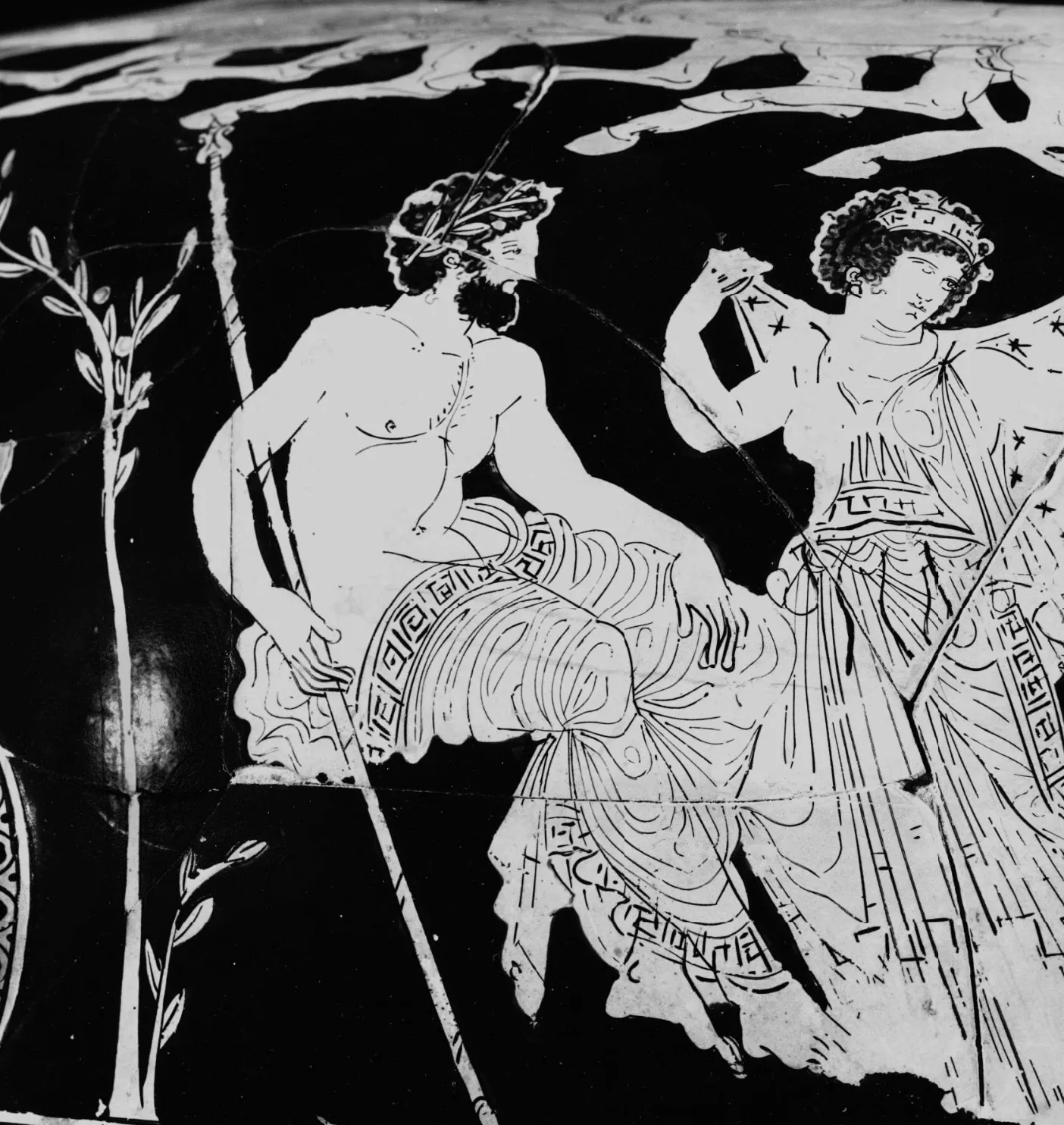

She is being embraced, the arms of her captor clasped around her waist. His movements rhyme with hers—heads bowed, right arms extended forward, his chlamys and her pleated robes both billowing in the wind as they ballet. He almost rests his head on her shoulder as they waltz in lockstep. The Meidias Painter on his late 5th-century name vase renders this scene with such exquisite sweetness that, on first impression, it might read more like an elopement than an abduction (fig. 1). Eriphyle, one of the daughters of Leukippos, seems entirely to acquiesce in Kastor’s plot to abduct and violate her. There seems to be a “total exclusion of violence”1—an “escapist” attempt, as J. J. Pollitt might contend,2 to sanitize the violence of the story amid the bloody backdrop of the Peloponnesian War (431–404 BCE).

But a more psychological reading of the Meidias hydria reveals darker undertones amplified by its disarming visual grace. Kastor’s embrace restrains Eriphyle at her core, her navel, locking her in his ill-meaning arms. Her unsteady legs give the impression that theirs is a coerced ballet. She lowers her head in quiet despair, perhaps a kind of learned helplessness, intimating that his advances are not welcomed nor reciprocated, that his hair is brushing her shoulder without consent. Her eyes are dim and downcast, a look of surrender; his are fixed on her, hungry, fantasizing. Is there really, as Pollitt suggests, “nothing to fear”?3 Eriphyle’s lack of overt resistance lends this dance of an abduction a chilling sense of inevitability. There is every indication of a one-sided relationship, an imbalance of power. That Kastor’s crime is a peaceful one—that he is effortlessly successful—makes it doubly disconcerting.

Eriphyle’s sister, Hilaeira, faces a similar fate (fig. 2). She is whisked away by an equine mass that, on the contour of the vase, appears centipede-like, its segments and angular appendages giving rise to a ticklish unease. Her captor Polydeukes has both hands on the reins, wielding total control over her destination and, by extension, destiny. His lips show the faintest suggestion of a smile, smug about having accomplished this dishonorable deed. Hilaeira, for her part, leans her head forward in silent protest, brows slightly furrowed and eyes burning with a hint of dull anger. However misleading her outwardly calm disposition might be, it fails to fully mask her mutely defiant expression. Her visage is decidedly not that of a damsel but that of a woman who knows she is losing her dignity.

The superficial grace of the hydria’s iconography, then, must not be mistaken for mere levity. The narrative of injustice that is the abduction of the Leukippides remains darkly present in the Meidias Painter’s iconographic program, only more insidious and, in its elegance, more disquieting. Indeed, this oblique, psychological approach to representing peril can inform our interpretation of the interior frieze from the Temple of Apollo Epikourios, Bassae (ca. 420–400 BCE), and the visual echoes of Classical carnage in Matteo di Giovanni’s Massacre of the Innocents (1488 CE). These depictions of crime or carnage each negotiate the boundary between objective representation and interventional aestheticization. They reveal that visual or contextual abstractions of violent imagery can mediate and strengthen its symbolic potency. They reflect, too, the uncomfortable reality that bloodshed and barbarity are often masked by—and coexist with—façades of serenity and veils of grace.

And those façades, those veils, can be powerfully deceptive. The mellow finery of the Meidias hydria’s imagery, for instance, leads Pollitt to predict an innocuous resolution to the Leukippides’ story.4 But there need not be overt, earth-shaking resistance on the part of the victim for a crime to be frightful. If the Meidias Painter cannot convince us of this fact, perhaps the task is better suited for Sir Lawrence Alma-Tadema, whose Roses of Heliogabalus (1888; fig. 3) echoes the hydria’s “florid style”5 both in spirit and in floral form. Alma-Tadema’s picture is an ornate treatment of horror: the richly clad figures in the foreground are not frolicking on a pink flower bed, as the artist might have us believe, but gasping for air in their final moments. As they perish, the Roman emperor Heliogabalus and his retinue indulge in fruit, wine, and music. Heliogabalus here suffocates his guests with an avalanche of rose petals, to which they, like the Leukippides, respond with only “a token of resistance.”6 In fact, some among the dying even wear looks of enjoyment, an oxymoronic tragedy: are they oblivious to their circumstances pre-anagnorisis, or have they coolly accepted their demise? In either case, there is a devastating absence of human agency. By masking barbarism with rosy allure, Alma-Tadema offers a striking counterexample to the sentiment that sweetness of visual vernacular translates to innocence of embedded narrative.

Nonchalant Heliogabalus, moreover, finds a direct analog on the Meidias hydria in calm, collected Zeus (fig. 4). He sits idly below Polydeukes and Hilaeira’s quadriga, entirely unfazed by the Dioskouroi’s misdeeds, the laurel of victory adorning his head recalling the blood-red flower above Heliogabalus’s ear. As the women are carried away, Zeus basks in whimsy, compounding their humiliation. Pollitt rationalizes his calm as “befit[ting his] status,”7 but this only worsens the optics of the narrative: two young women resignedly accept their plight while the King of the Gods offers tacit approval—such a headline hints that there is much to fear. His inaction permits the other bystanders to follow suit in watching passively.8 With Alma-Tadema’s chilling canvas in mind, the Leukippides’ lack of resistance, want of assistance, and implied loss of agency take on an even more sinister tone. The trouble with the Meidias vase is that without knowing what came of the Leukippides’ abduction, attempts to link its iconography with the nature of those consequences are purely speculative. It finds a contextual and contemporary counterpoint, however, in the Centauromachy panels from Bassae and their allusions to Peloponnesian conflict. The brutality and outcome of that civil war, intimated by the Bassae frieze to be a product of Periclean imperialism,9 is well-recorded. Certainly the cruelty of battle is on full, gut-wrenching display in the frieze’s scenes of savage combat. But it takes on a heightened emotional valence, an even more poignant pathos, in its occasional moments of grace.

Among the most affecting passages from the Bassae reliefs is found on slab 522 (fig. 5). We see a centaur attempting to restrain a Lapith mother whose child, perched on her left arm, latches onto her neck for dear life. Framing their nightmarish tango is the woman’s drapery, exquisitely billowing in the wind, expertly described in differing depths of marble. It leaves one breast exposed, accentuating the emphasis on her maternity. Rather than melting into a frenzied, desperate mess, however, the Lapith maintains stern composure. The heroic diagonal of her body recalls the light-footed warrior in south metope 27 from the Parthenon (fig. 6), a reference that augurs well for the outcome of her struggle. Her movement appears measured, almost balletic, exemplifying the lofty ideal of sophrosyne that Greek culture so prized. Beyond her elegant chiastic form, though, the courage in this mother’s gaze lends hope that she will triumph. She locks eyes with the centaur, regarding him with unyielding intensity and unshakeable resolve, pouring life and love and soul into her resistance, imbuing it with a potent, unwavering maternal strength that the centaur cannot match. He lacks her conviction, her burden. He may be in this for the thrill, but she is in this for her baby. That baby clings to her with total trust, with equal courage, head bent slightly forward to defy the whipping wind. She will save him, her eyes seem to say, and she will do so with grace.

This narrative from slab 522 is rendered with such technical virtuosity that the passage of time, both within the picture and without, seems to stop in deference. Deference to the artist, yes, but also deference to the astounding sophrosyne of the brave young mother he has immortalized in Arcadian marble. Is this a realistic depiction of the battlefield? Is our optimism about the Lapith’s victory a naïve, unfounded fantasy? Given the unthinkable number of casualties in the conflict being mythicized in these panels—the Peloponnesian War—surely the sculptor had an answer in mind.10 But in asking us to abandon these pragmatic concerns to behold the virtuous grace of this woman’s resistance, his depiction of violence becomes heartbreaking all the more. It strives not for documentary objectivity but for a kind of psychological gameplay, weaving in and out of the real and the ideal to offer false hope—a maneuver that, in and of itself, illustrates a ruthless aspect of war.

The steady tempo of slab 522 defies the breakneck pace of mortal combat, the whirlwind surge of an adrenaline rush. It prolongs the struggle in “bullet time,” recalling the slow-motion bullet-dodging sequence in modern cinema.11 It keeps our hearts pounding and palms sweating. It invites our sympathy, giving us a cruel beacon of hope when we know this to be in all likelihood a losing fight. Applying this paradigm of analysis to the abduction on the Meidias hydria, the tone of the vase entirely shifts. Similar questions arise: is the Meidias Painter fooling us with his “total exclusion” of overt violence? Is he sanitizing peril with beauty, or is he weaponizing beauty to intimate unthinkable peril? At once the hydria and the Bassae frieze become an unlikely yin-yang couple—one whose apparent grace hides obscene violence, another whose apparent violence hides harrowing grace. Both are premier examples of psychological drama avant la lettre.

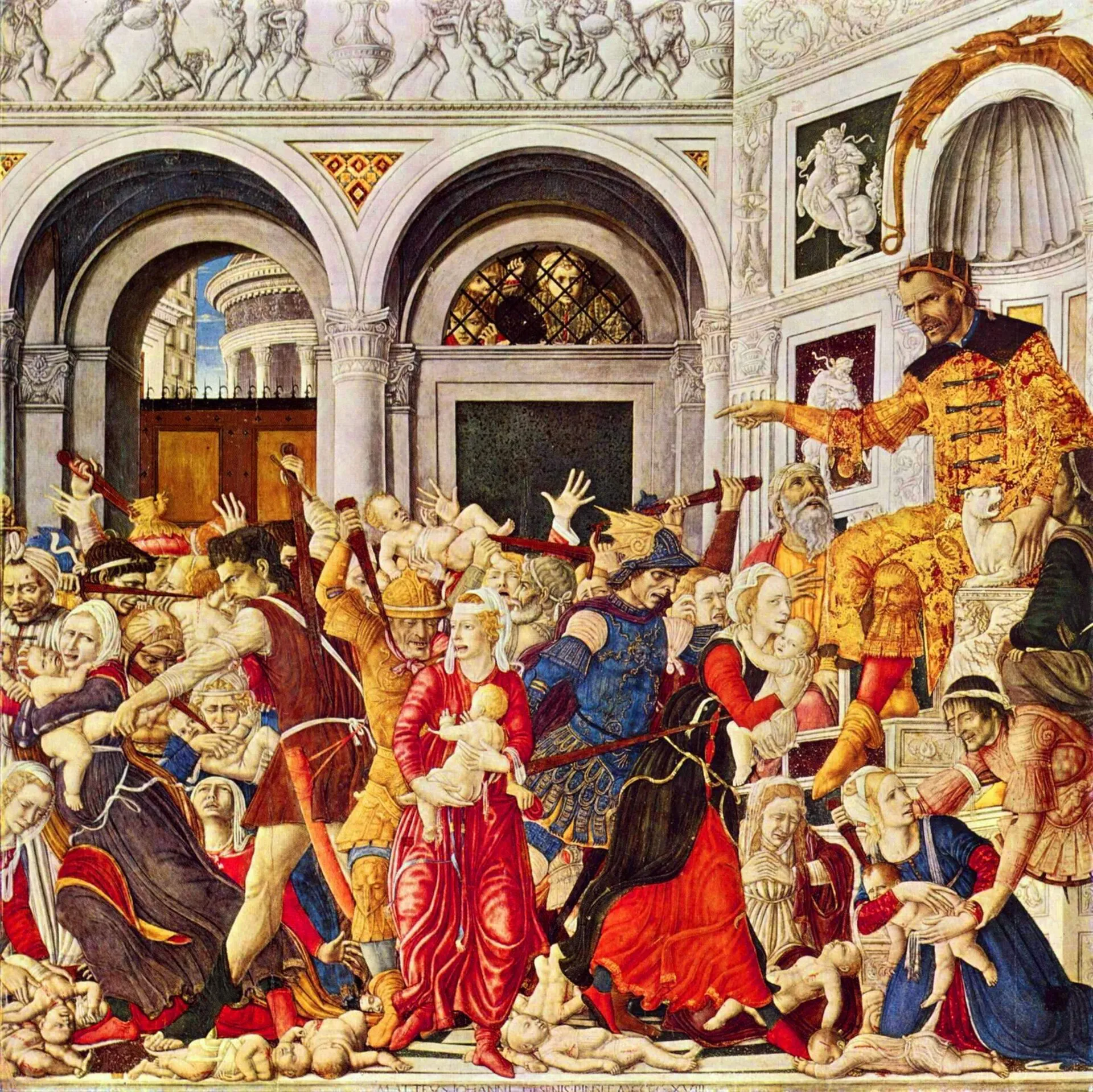

Remarkably, nearly a millennium later, the two works reunite in spirit in a painting made across the Adriatic Sea. In the second half of the 15th century, Alfonso II of Naples commissioned the Sienese master Matteo di Giovanni to paint several versions of the Massacre of the Innocents.12 One such commission (fig. 8) roughly coincides with the 1480 slaughter of the citizens of Otranto, in southeastern Italy, by Ottomans who sought and failed to convert them to Islam.13 Matteo’s product, once housed in the same church that held the relics of the Otranto Martyrs, transfigures the violence at Otranto into a biblical abstraction, much like Bassae maps the Peloponnesian conflict onto a mythical one. His picture is unique in Quattrocento painting for its depiction of unfettered brutality. Equally compelling, however, are the echoes of Meidias and Bassae that lay within.

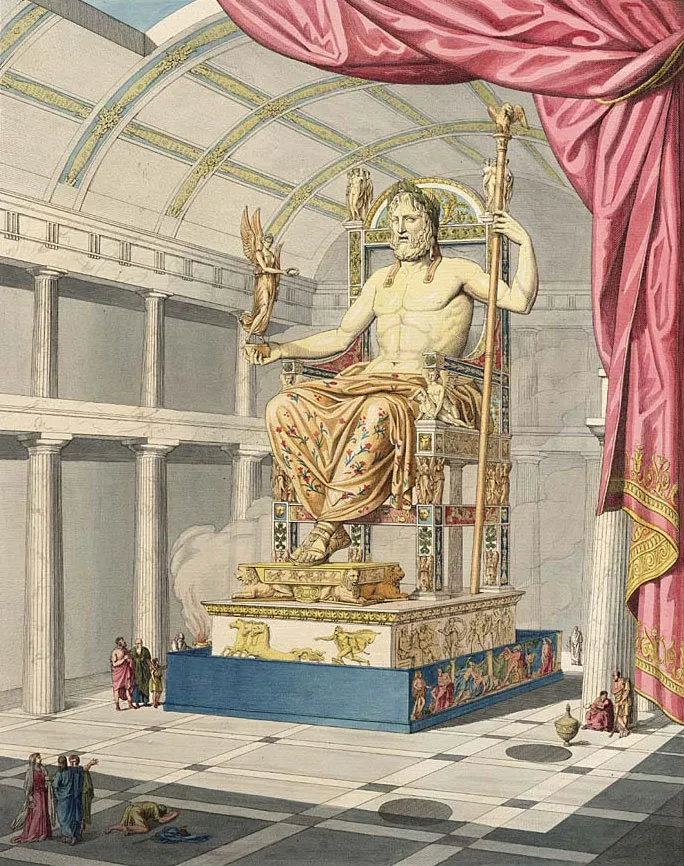

Matteo’s composition throbs. Its writhing, swelling mass of figures is so dense we can hardly match heads to bodies. The commotion is confused, illegible, like termites swarming out of a disturbed nest. Lethal weapons abound. Body heat saturates the air. Few inches of foreground are spared from the weight of cold, lifeless infant children, and even fewer are left untrodden by the frantic feet of mothers in flight and terror. The atmosphere brims with malignancy and claustrophobia, an unease intensified by the wretched-looking older children clinging onto the semicircular grille at top center. We, as viewers, are situated in a similar position: locked outside the hive of bodies and powerless to stop the carnage. Presiding over this bloodbath, as consistent with the Massacre’s description in Matthew 2:16, is an imperious Herod-figure of monstrous proportions, more beastly than human (fig. 9). His is a Satanic visage wizened by cruelty and vice. Those furrowed brows, that malevolent gaze, betray an impatience with the pace of the killing. The color scheme of his garish robes seems to echo the event itself: indiscriminate splashes of red desecrating pristine, golden luxury. His status, stature, and throne remind of Phidias’s colossal statue of Zeus at Olympia (fig. 10), except Matteo’s Herod seems ready to unleash on his audience deafening thunder and deadly lightning.

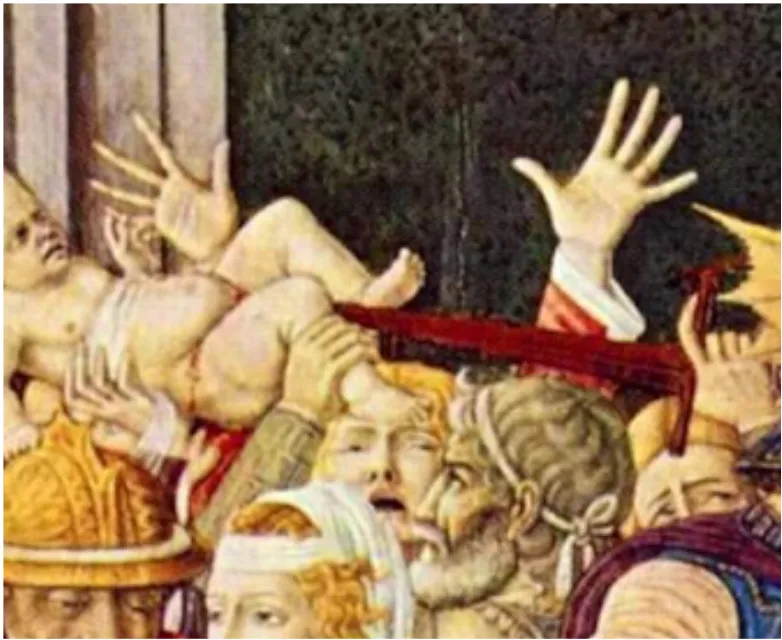

Children lie sprawled on the floor, dead or dying, fresh crimson blood oozing from their wounds. Matteo di Giovanni’s attention to detail is at once extraordinary and haunting: below the left shoulder of the boy lying prone at lower right, we see four tiny fingers peeking out—a hand with no one to hold it. His shroud is his pleated, diaphanous robe. At the lower left corner of the composition crouches a grieving mother whose tears fall to meet the blood of her dead baby. Her child’s posture both physically and spatially mirrors that of the struggling Amazon in slab 541 of the Bassae frieze (fig. 11), who shares his outstretched arm, his slightly open mouth, his awkward, unnatural backward bend. In this sense, the boy and the Amazon exist in the same liminal moment, that storied transition from the last breath to the dark beyond. Crossing the Styx. Capitulating to Death. Suspended, like their bodies, in limbo. Punctuating the horizon line, meanwhile, is a dance of anguished hands. One fully sprawled-out hand anchors the center of the composition, neatly contrasting with the dark stone paneling behind it. Its owner takes effort to locate: a woman with flaring nostrils and despairing eyes, mouth agape in exclamation or prayer; following her anatomy leftward yields the discovery of her other hand, also outstretched. In this sense, she is Matteo’s “answer” to the culminating scene from the Centauromachy at Bassae, wherein a Lapith extends both her arms in sheer distress (fig. 12).

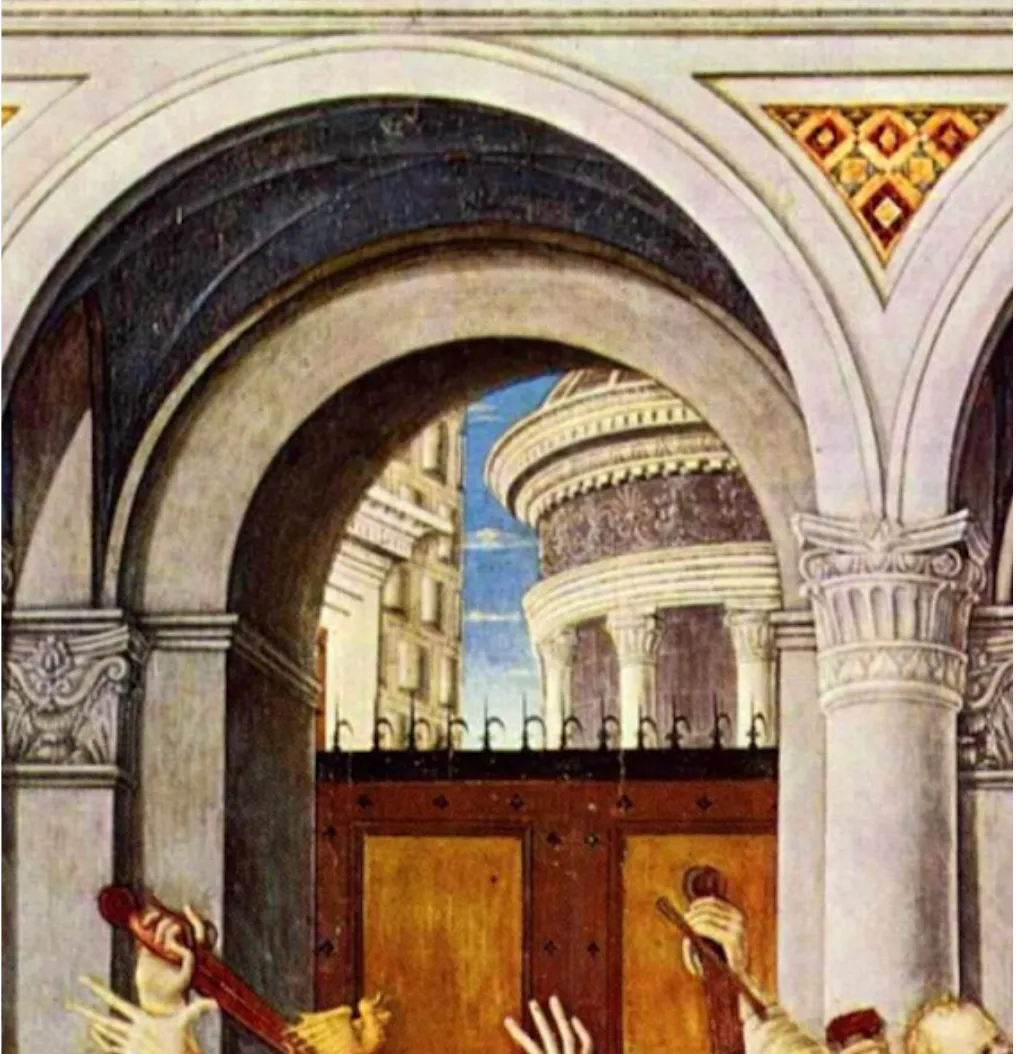

These are grieving mothers, frightened mothers—each a far cry from the composed Lapith on slab 522. Where, then, is the “Meidias,” the disarming grace? We find it in the background, through a classicizing archway supported by engaged Corinthian columns. There Matteo offers a glimpse into the outside world, which, with its partly visible Pantheon-like structure, might as well date to classical antiquity. And in that world—access to which is blocked by a hefty wooden door—exists a sliver of ironic serenity: clouds scudding blithely across a cerulean sky (fig. 13). In fact, taken together with the geometric order of the classical architecture below that sky, this could be described as a sliver of perfection. But what a cruel joke! There is carnage in the foreground; there is a slaughterhouse in the foreground; there are dead and dying two-year-olds in the foreground. Zeus might be too vain to show concern for the Leukippides, and Alma-Tadema’s Heliogabalus might be sufficiently depraved to recline and relax as his subjects are smothered. But how can Nature remain pristine, unfazed, in the face of such barbarity? Indeed, those beautiful skies are framed by misery on three sides: from below, by the massacre itself; from the right, by the grille with the anxious children, who may be losing their siblings; and from above, by a Greco-Roman frieze featuring scenes of battle not unlike those from Bassae. Matteo di Giovanni reveals to us the horrible truth that unspeakable carnage and consummate grace can, and often do, coexist. That nightmarish peril and ineffable beauty can, and often do, melt into one.

It is terrifying that Herod could walk off this killing field into the warm embrace of the Sun, could look up and enjoy the dignified waltz of floating clouds. But it is equally terrifying that the Lapith mother at Bassae can display such sophrosyne, embody such poise and love and courage, in the split-second before she could lose her young boy. It is equally terrifying that World War I soldiers can be congenial brethren on Christmas and merciless killing-machines the following week (fig. 14). It is likewise terrifying, then, that Eriphyle can helplessly ballet her way off the beautiful Meidias hydria, painfully aware of the lust and obscenity she is poised to face. But it is also the truth, and it reflects in each of these pictures a multivalent “inner life.”14

And it is a truth to which each of these artful fictions—these abstractions, transpositions, and mythicizations of crime and carnage—leads us ever closer. Perhaps, in an era marred by traumas of plague and war, the Meidias Painter sought to interrogate precisely this uncomfortable union of grace and violence. Read in this vein, he invites us to uncover the cloistered anxieties and insidious discord brewing behind his, and late 5th-century Athens’s, “florid” façade. He urges us to entertain the possibility that his balletic Eriphyle stands for the tragedy of helpless surrender and the irony of beautiful peril. Like Alma-Tadema, Matteo di Giovanni, and the sculptors at Bassae, he taunts us with these possibilities and alerts us to their urgency. And, as with the fates of his tragically exquisite Leukippides, he leaves them open, unresolved.

Footnotes

-

Lucilla Burn, The Meidias Painter (Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1987), 16. ↩

-

Jerome J. Pollitt, Art and Experience in Classical Greece (Cambridge, England: Cambridge University Press, 1972), 125. ↩

-

Ibid., 123. ↩

-

J. J. Pollitt, Art and Experience, 123. ↩

-

J. J. Pollitt, Art and Experience, 123. ↩

-

Ibid. ↩

-

Ibid. ↩

-

The Meidias Painter’s illustration of the “bystander effect” reminds of an incident at Richmond High School, a mere hour north of Stanford, in 2009. On homecoming night, a 16-year-old girl was gang raped at the hands of at least six boys in the presence of some twenty observers, none of whom contacted authorities. Their silence was seen as translating to complicity. Chillingly, the victim was disarmed by her attackers’ initially “polite” behavior—their veil of grace. People v. Montano, No. A139919, Cal. Ct. App. (2019). ↩

-

The Bassae frieze contains a number of iconographic quotations from the Parthenon’s pediment, as if to hold the Parthenon and Pericles by proxy responsible for the outbreak of civil war. The chiastic form of the Lapith woman in slab 522 (fig. 6), for example, echoes that of the warrior in south metope 27 from the Parthenon (fig. 6). ↩

-

Barry S. Strauss, in his Athens after the Peloponnesian War: Class, Faction and Policy 403–386 B.C. (Ithaca: Cornell University Press, 1987), estimates 18,070 military casualties alone. ↩

-

“A Brief History of Bullet Time,” The Flash Pack. ↩

-

Mario Sapio (ed.), Il Museo di Capodimonte (Milan: arte’m, 2012), 186. ↩

-

Iván de Vargas, “The 800 Martyrs of Otranto,” Zenit, 2013. ↩

-

This may well be the “inner life” that Sir Mortimer Wheeler had searched for, and failed to find, in the Parthenon. Mortimer Wheeler, Roman Art and Architecture (New York: Thames and Hudson, 1964), 12. ↩